While almost anyone is taught that the Earth is a sphere with all of us somehow glued to it by gravity, the reality of our circumstance did not really begin to sink in until the famous frame-filling Apollo photograph of the whole Earth--the one taken by Apollo 17 astronauts on the last journey of humans to the Moon.

It has become a kind of icon of our age. There's Antarctica at what Americans and Europeans so readily regard as the bottom, and then all of Africa stretching up above it: You can see Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Kenya, where the earliest humans lived. At top right are Saudi Arabia and what Europeans call the Near East. Just barely peeking out at the top is the Mediterranean Sea, around which so much of our global civilization emerged. You can make out the blue of the ocean, the yellow-red of Sahara and the Arabian desert, the brown-green of forest and grassland. [ View related excerpt ]

And yet there is no sign of humans in this picture, not our reworking of the Earth's surface, not our machines, not ourselves. We are too small and our statecraft is too feeble to be seen by a space-craft between the Earth and the Moon. From this vantage point, our obsession with nationalism is nowhere in evidence. The Apollo pictures of the whole Earth conveyed to multitudes something well known to astronomers: On the scale of worlds--to say nothing of stars or galaxies-- humans are inconsequential, a thin film of life on an obscure and solitary lump of rock and metal.

It seemed to me that another picture of the Earth, this one taken from a hundred thousand miles farther away [beyond the orbit of Neptune], might help in the continuing process of revealing to ourselves our true circumstance and condition. It had been well understood by the scientists and philosophers of classical antiquity that the Earth was a mere point in a vast encompassing Cosmos, but no one had ever seen it as such. Here was our first chance (and perhaps also our last for decades to come). [...]

From this distance the planets seem only points of light-- even through the high-resolution telescope aboard Voyager. They are like the planets seen with the naked eye from the surface of the Earth-- luminous dots, brighter than most of the stars. This is how the planets would look to an alien spaceship approaching the Solar System after a long interstellar voyage. You cannot tell merely by looking at one of these dots what it's like, what's on it, what its past has been, and whether, in this particular epoch, anyone lives there. [...]

But for us, it's different. Look again at that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was. lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar", every "supreme leader", every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there--on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of the other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves. [...]

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we've ever known.

Excerpt from

Carl Sagan (1994)

Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space

New York: Random House

We have held the peculiar notion that a person or society that is a little different from us, whoever they are, is somehow strange or bizarre, to be distrusted or loathed. Think of the negative connotations of words like alien or outlandish. And yet the monuments of cultures of each of our civilizations merely represent different ways of being human. An extraterrestrial visitor, looking at the differences among human beings and their societies, would find these differences trivial compared to the similarities. The Cosmos may be densely populated with intelligent beings. But the Darwinian lesson is clear: There will be no humans elsewhere. Only here. Only on this small planet. We are a rare as well as an endangered species. Every one of us is, in the cosmic perspective, precious. If a human disagrees with you, let him live. In a hundred billion galaxies, you will not find another.

Human history can be viewed as a slowly dawning awareness that we are members of a larger group. Initially our loyalties were to ourselves and our immediate family, next, to bands of wandering hunter-gatherers, then to tribes, small settlements, city-states, nations. We have broadened the circle of those we love. We have now organized what are modestly described as super-powers, which include groups of people from divergent ethnic and cultural backgrounds working in some sense together-- surely a humanizing and character-building experience. If we are to survive, our loyalties must be broadened further, to include the whole human community, the entire planet Earth. Many of those who run the nations will find this idea unpleasant. They will fear the loss of power. We will hear much about treason and disloyalty. Rich nation-states will have to share their wealth with poor ones. But the choice, as H.G. Wells once said in a different context, is clearly the universe or nothing.

The choice is stark and ironic. The same rocket boosters used to launch probes to the planets are poised to send nuclear warheads to the nations. The radioactive power sources of Viking and Voyager derive from the same technology that makes nuclear weapons. [...]

A few million years ago there were no humans. Who will be here a few million years hence?

Carl Sagan Cosmos (1980, p.339)

We are set irrevocably, I believe, on a path that will take us to the stars--unless in some monstrous capitulation to stupidity and greed we destroy ourselves first.

Carl Sagan Broca's Brain (1979, p.368)

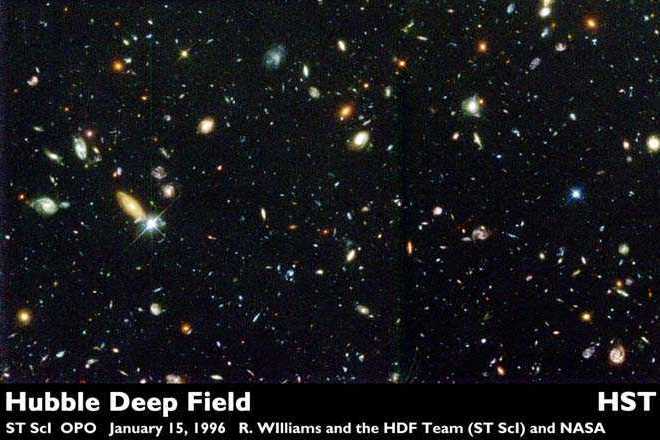

A token of the astonishing richness of the Cosmos. Virtually every object seen in this spectacular photograph obtained by the Hubble Space Telescope is a galaxy containing billions of stars. The field of view of this picture is a little piece of the sky less than one percent of the apparent angular area of the Moon. It therefore represents only about one hundred millionth of the sky.

Ann Druyan suggests an experiment: Look back again at the pale blue dot. Take a good long look at it. Stare at the dot for any length of time and then try to convince yourself that God created the whole Universe for one of the 10 million or so species of life that inhabit that speck of dust. Now take it a step further: Imagine that everything was made just for a single shade of that species, or gender, or ethnic or religious subdivision. If this doesn't strike you as unlikely, pick another dot. Imagine it to be inhabited by a different form of intelligent life. They, too, cherish the notion of a God who has created everything for their benefit. How seriously do you take their claim?

Carl Sagan Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space (1994)

We have come far in 3.6 million years, and in 4.6 billion and in 15 billion. For we are the local embodiment of a Cosmos grown to self-awareness. We have begun to contemplate our origins: starstuff pondering to the stars; organized assemblages of ten billion billion billion atoms considering the evolution of atoms; tracing the long journey by which, here at least, consciousness arose. Our loyalties are to the species and the planet. We speak for Earth. Our obligation to survive is owed not just to ourselves but also to that Cosmos, ancient and vast, from which we spring.

The finale of Carl Sagan's Cosmos (1980)

| [ CarlSagan.com ][ Tribute to Carl ] | [ Home ][ Memes ] |